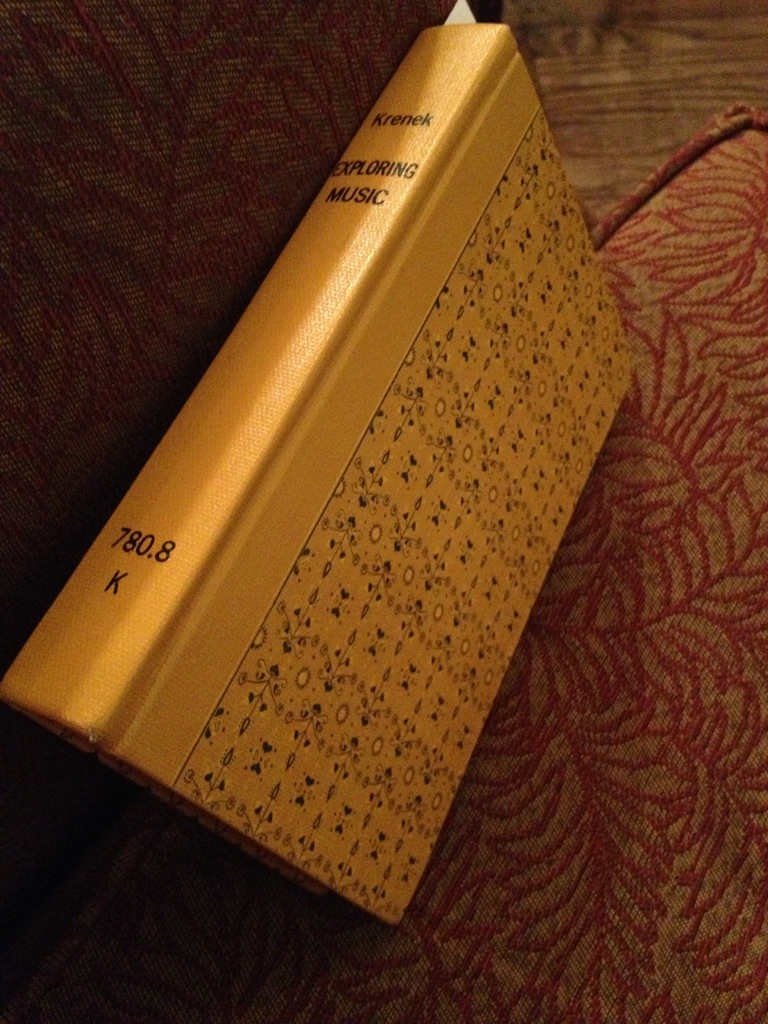

I’m combing my way through Krenek’s set of essays Exploring Music, and it’s providing some great insight into the man and his beliefs. His vignette on Milhaud that I wrote about before was really cool. I’m currently digesting ‘New Humanity and Old Objectivity’ and some of his views on vernacular forms of art (pop music in this case) are astonishingly backwards. The genre or medium of a work should not be taken as a way to blanket judgement of quality. I turn it over to Krenek to show you what I mean:

Now in music the age has found the art that satisfies all its needs–popular music. As far as its production and consumption are concerned it corresponds perfectly to the other present-day principles of creation and running. Production takes on a conveyor-belt system–wach of the numerous operatives taking part in the process carries out only one ‘repeated, thoroughly leaned action’ as they say in the collective contracts for a given category of industrial workers. We hear that there are refrain-specialists, verse-specialists, specialists in harmonizing the half-finished product, others specially skilled in producing witty or imposing titles; there are others who do the rhymes and specialists in radio, salon, jazz and other orchestration who then put the finished project into its normal commercial package. It is rather like a cloth factory where at one end the wool is taken off the sheep and at the other the finished material emerges. But in this case the part of the fleeced lamb is played by the unconscious consumer.

This art is, of course, adjusted to the conditions of a large turnover; the goods are mass-produced, so that production costs are lowered the articles are almost interchangeable types so that you can get away with an unsubtle, dull feeling for the type and are not disturbed or surprised by individual traits; the material is easy to understand and the words satisfy the hunger for scraps of information in a particularly accessible field half-way between sex and sentiment.

But of course it must not be thought that this art is deliberately produced because there is a need for it, and that its creators could write differently if they chose. On the contrary, here as elsewhere the demand is created by the producers, for at bottom the public is indiscriminate, ready for anything. The writers cannot do anything else because they themselves cannot rise above this sphere and one cannot but be convinced that they are doing the best they can, for no artist can deliberately write below his real level. If anybody says he could just as well write symphonies as pop songs and only writes the songs because they pay better, he is lying, perhaps unconsciously, and ruining his character without improving his talent.

Seething through this passage is condescension for writers of pop songs, and popular forms themselves. Krenek states that, “if anybody says he could just as well write symphonies as pop songs and only writes the songs because they pay better, he is lying,” but is the inverse true at all? Could Krenek have written a single song out of Exile on Mainstreet? Additionally, the idea that multiple parties coming together to produce a musical track “fleeces the unconscious consumer” is utterly false. Does the help Al Green, The Supremes, Beyoncé, and so many more artists receive over the course of producing their albums inherently reduce the value of their music? There is remarkable depth to some popular songs, this is not a new idea.

Couldn’t write a symphony.